A few weeks ago my good pal Peter Megginson came over to Scrum Hall (my dining room) and set up a game for the two of us to play with my other good pal, Steve Braun. He gave me a lot of choices ahead of time for the type of game he could put on, including many periods and genres I had never tried before. Peter is one of my wargaming buddies who likes to play "historical" games in addition to all of the "genre" games (fantasy, sci-fi, etc.) I tend to gravitate toward, and so this was an opportunity for me to branch out and try something new.

We ended up settling on a game centered on a fictitious Vietnam War-era operation. I can't claim to remember all of the details of the scenario at this point, but the gist involved one side playing the Americans who had choppered in near a village in Laos to try to extract any survivors from a downed huey. The other side played VC who saw the US chopper go down and were looking to take its crew prisoner. Scoring was based on the number of downed crew members each side could find (they were hiding in and around the village) and get safely off the side of the playing area each player deployed from. I know the American side could also score points by finding and destroying ammo and weapon caches found around the deserted village (I can't recall if the Vietnamese player have a comparable way of scoring extra points). Peter used a homebrewed mélange of Disposable Heroes and The Long Road South for the rules of our game.

The scenario itself hints at my ambivalence when it comes to playing games like this. Make no mistake: I had a fun time, and I will play almost anything that puts me at a table with Peter and Steve, but I'd be lying if I said I didn't have mixed feelings about playing a wargame set in Vietnam. It's not easy for me as an American to play American soldiers in Laos--where Americans should never have been in the first place. As I observed to Peter and Steve more than once during the game, the Americans aren't exactly the good guys here.

That might be part of the reason why, despite loving wargames, I prefer genre gaming over historical gaming: the backstory for each made-up conflict can be as unambiguous as you like. And even if you like to add some "realism" to those fantasy or sci-fi conflicts by making the motivations of the antagonists shades of grey rather than stock good and evil, you at least aren't having to confront the uncomfortable real world echoes that games set in actual periods of conflict can force you to grapple with. I, for one, would have real difficulty getting excited about a Civil War-era game in which I had to play Confederates, given the fact that we're still dealing today with the legacy of that conflict and its unambiguously racist impetus. And, fair or not, I admit that I'd have some questions about somebody who wanted to play the South in such a game. Maybe I'm just not interested enough in military history to achieve the cold, analytical distance needed to find pleasure in recreating battles in which the morality so clearly favors one side.

Gaming in other periods does not present these challenges for me, and that's probably more a testament to my poor education about the conflicts between Vikings and Saxons or the 100 Years War or Alexander the Great's conquests. But I do personally know Americans who fought in Vietnam, and I have Vietnamese friends and acquaintances whose families were traumatized by the war. One of my Scrum Club mates has a Vietnamese wife, and that, too, has made me wonder if he cringed when he heard I was playing a game with toy soldiers set in Vietnam. I'd hate to offend by trivializing something that hits very close to home for him.

I try to go through life with as much self-awareness as possible, and so I feel compelled to honestly acknowledge in this post that, despite all of the pleasure this hobby has brought me in the past six years since "discovering" it, my relationship to it isn't uncomplicated.

And reconciling that basic paradox--I love wargaming but hate war--is a challenge and something of a personal enigma. I went to numerous protests in opposition to the war in Afghanistan and Iraq. I hope, but can't be confident, that if I was a young man during the Vietnam War I would have done the same. My dad was a brawler in his youth, and never shied away from a fist fight or physical confrontations, but he was also quite clear with me that he was very thankful that the Korean War effectively ended a few months before he turned 18 and would have been eligible to be drafted. He had no desire to go to war, and never romanticized it with me.

My mother's two older brothers served in the navy in WWII: one came back an alcoholic, impotent from malaria contracted in the Philippines; the other died six weeks before war's end in the Battle of Okinawa when six kamikazes eventually sunk the destroyer he had served on for the previous four years. Nobody in my family glamorized those men's service or sacrifice.

That said, I was obsessed with WWII as a child and eventually the Vietnam war in my early teens. I had a grocery bag full of army men in the 1970s that could entertain me for full days, and for a while enjoyed few things more than running around the neighborhood playing war with a plastic M-16 that I know my mom absolutely loathed. I even thought as an early teen that I might want to be a helicopter pilot for the Army. Eventually, the more I learned about and understood the horror of all wars--and that precious few of them were fought on defensibly righteous grounds--I grew less enamored with those conflicts. Yet war is still fascinating to me on a fundamental human level. I took a course called Vietnam War Literature in college with my favorite professor, Stephen Wilhoit, and it was there that I first read Tim O'Brien's books, which profoundly shaped not only my understanding of war but what kind of writing I aspired to do as a young man of letters. It's hard to maintain a romanticized mindset about the Vietnam War after a course like that one.

|

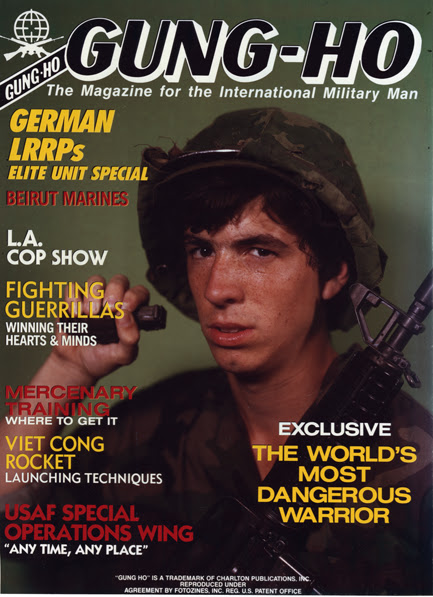

| Even when I had this photo taken at an amusement park booth at age 13 it was done with a bit of self-aware irony regarding my conflicted feelings on the subject. |

So, I approached our game by trying to put myself back in the mind frame of that young kid who would have enjoyed spending the entire afternoon scratching around in the dirt and grass of the backyard with his best friend at the time, Jerry Bell, creating battles for those green army men we pitted against one another on those bygone summer days. Peter brought silly hats for us to wear at the game table--a bit of a trademark of his GMing style--which also helped make it hard to take any of it too seriously, as well.

Without further rumination, I'll share some photos from our game. These were shot by either Peter or myself. No matter the setting or period, Peter puts on fun, cinematic games, and I did have a great time this particular afternoon, despite what all of the soul searching above may suggest. I already have plans to run my own game set in the Vietnam War era...but to make it all a little easier for me, I'm using a set of rules in which the dark minions of Cthulhu figure prominently, creating a bit of psychological distance from the historical facts. I mean who hasn't wanted to skulk through the jungle and shoot M-79s at Lovecraft's Deep Ones?

|

| Bird's eye view of the battlefield before we deployed the forces on it. |

|

| Peter setting everything up... |

|

| Steve and Peter |

|

| Some of my special forces entering the village to look for the downed huey crew. |

|

| We found the chopper's pilot hiding out among these ruins. We managed to get him off the play area to safety. |

|

| We called in some smoke to give us cover at one point. |

|

| Your humble scribe and Steve |

|

| When searching this building a tiger jumped out and attacked! |

|

| The Vietnamese made short work of it. |

|

| We later called in an airstrike on a patch of jungle from which we kept taking sniper fire. |

|

| Me again with Peter |

|

| The end of a fun day...The Americans won this round on extra points for destroying some ammo caches. |

=================

===============================================

=================

The hats are good; the Communist party t-shirt is excellent. When the tiger appeared, I hope someone yelled "I'M NEVER GONNA LEAVE THE BOAT! I'M NEVER GONNA LEAVE THE BOAT! I ONLY WANTED SOME MANGOES!" I understand your ambivalence regarding playing near-contemporary war games. I find myself cringing quite a bit when I see my daughter playing Call of Duty, though had it been available when I was a teen... And like you, I knew people who were younger than my parents, but who had fought in the war and who would sometimes share their thoughts and experiences; and in time I came to know people from Laos and Vietnam who had come to America because of the violence done to their countries by the US. This is maybe an unanswerable question, but are their ethical considerations in a rule set for a game like this? Are there strengths or weaknesses awarded to sides based on immutable characteristics such as morale or devotion to cause, "righteousness" self-righteousness, or decidedly negative motivations, etc.? Particularly in a conflict like Vietnam, including its spillover into Laos and Cambodia, there are so many powerful motivators for the people involved who found themselves in the fight. ... [phew...enough ethical quandaries] Well, I can understand better now why you prefer fighting monsters and trolls, even if, or especially if, you can use M-79s. ;-)

ReplyDeleteSorry for taking so long to respond to this very thoughtful reply, Mike. I can't say I'm an experienced enough of a wargamer to speak to the myriad ways in which a set of rules might try to tackle some of what you've outlined in terms of "gamifying" the characteristics you mention. When and if I've seen that sort of thing tackled at all it has typically been through a Morale mechanic, which is very common part of most wargames. The ways in which Morale is incorporated, how it gets "tested," and the results of flagging or increasing morale can vary greatly from one set of rules to another, but if I was designing a set of rules (or even just a scenario to be played with an existing set), I would certainly look for ways to model some of what you describe using a Morale trait for units/figures. It would seem to me, to take a concrete example, that North Vietnamese soldiers should have some basic advantages in terms of their morale: it's their country, they know it better than their adversary, and they have a righteous cause. Where the U.S. soldier, at least in some situations, might be more motivated by simply staying alive, and passing or failing a morale check might have very different consequences or results for those different types of troops. Those would be important considerations that I would want to capture or have reflected in a game's rules or a scenario's design, but that definitely is just one approach to gaming. Others may prefer to keep the rules themselves fairly neutral, with less of a "simulationist" approach to reflecting troop "psychology." Some game designers and/or players might want to stress a whole other set of criteria or concerns (e.g., adequately capturing the performance of various sorts of military hardware, etc.).

DeleteFor another perspective, I have one particular friend who hates the imposition of Morale rules in fantasy games. He believes that it limits him from having his figures behave "heroically" and doing everything he might want to try to do at the table. I personally prefer a bit more "psychological realism" in my games. If you see a 30-foot-tall fire-spewing lizard charging at you, there should be some way within the game of capturing/conveying the consequences of such an experience. I personally would find it boring if nobody ever reacted (fear? dread?) at the prospect of being reduced to a cinder or to seeing your companions fall one by one to the axe of a rampaging minotaur. That shit should scare the hell out of almost anybody, and I want my games to try grapple with that at least on some level.

Mate i found that a very enjoyable and relatable read.

ReplyDeleteBut where's the info about the actual game lol